biographical notes

|

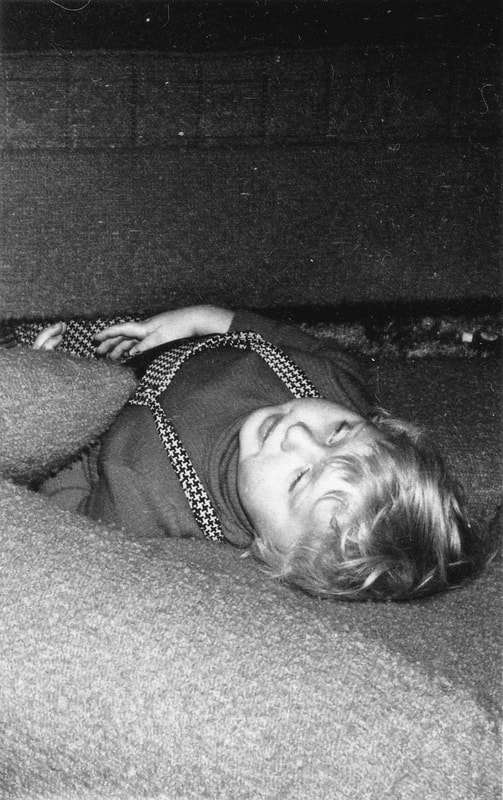

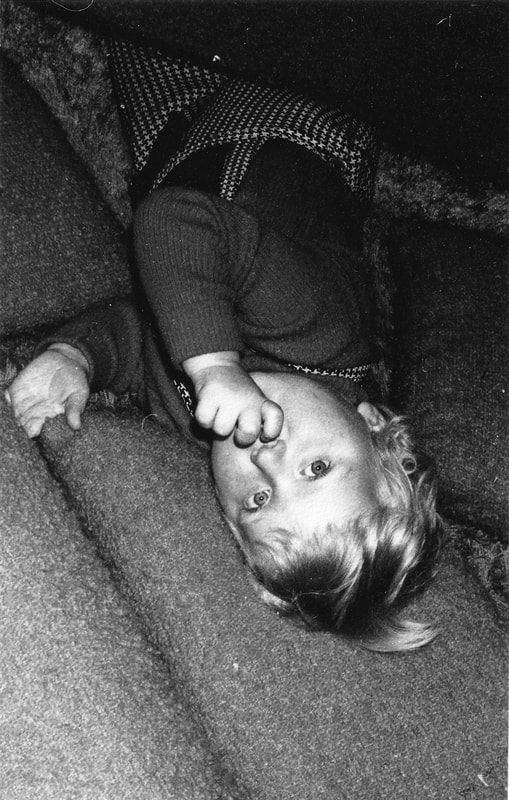

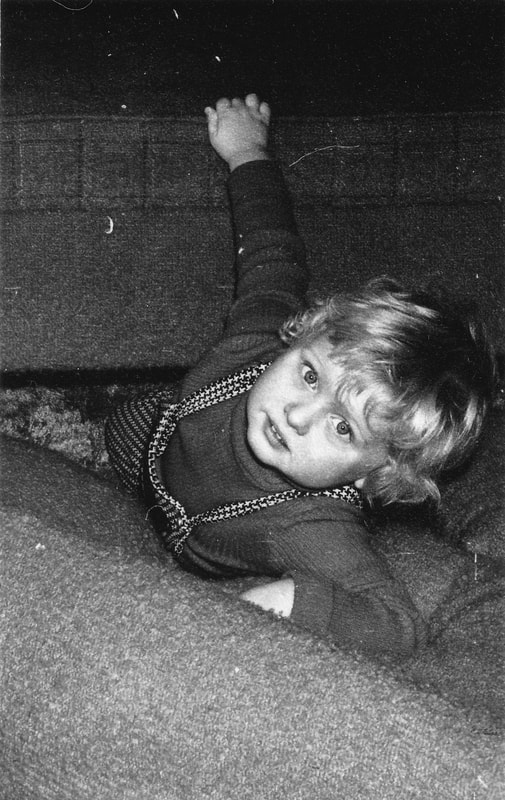

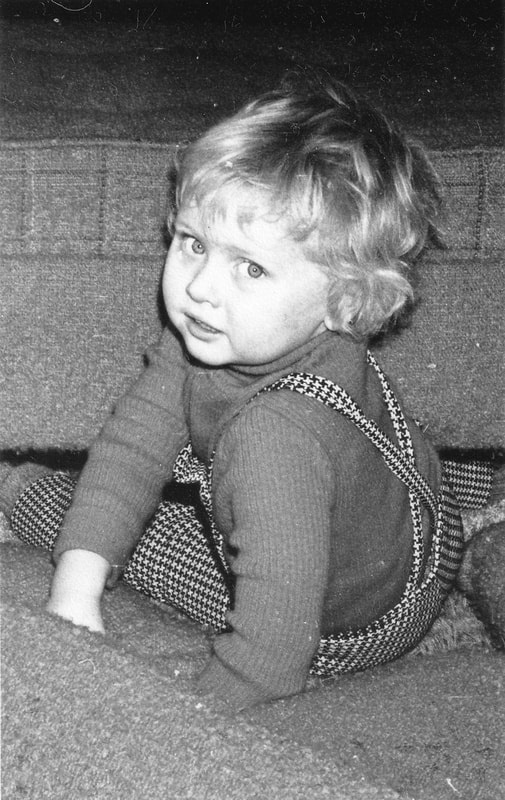

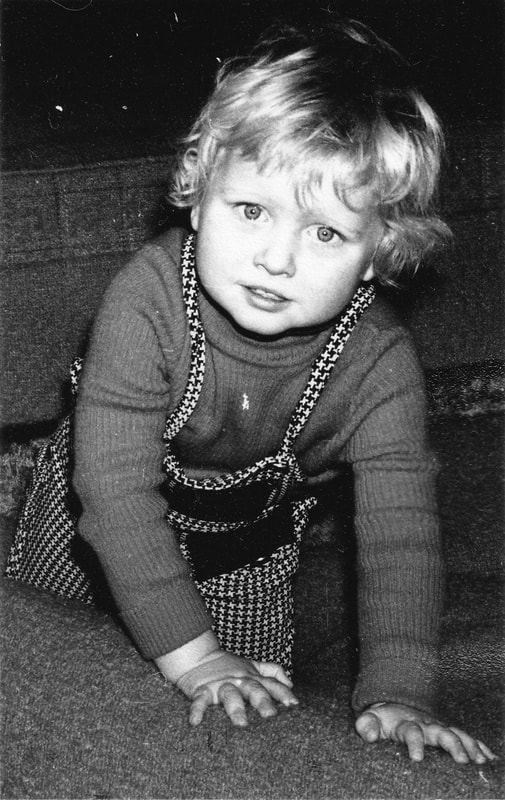

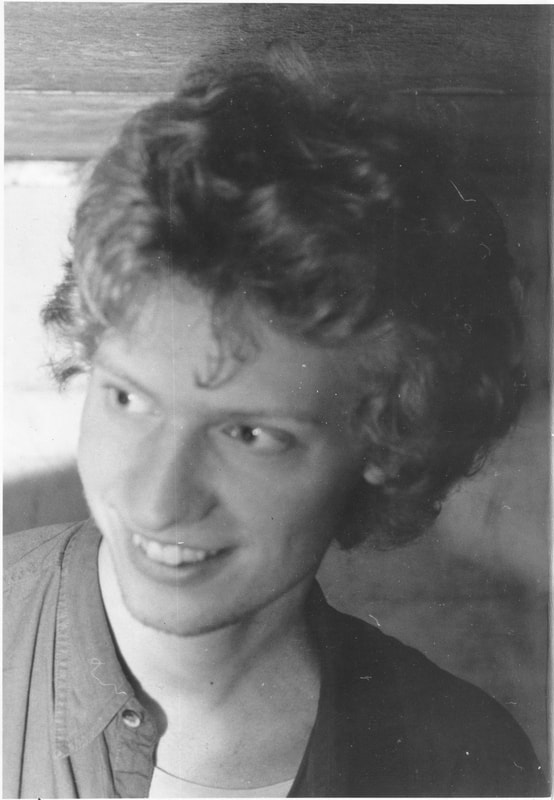

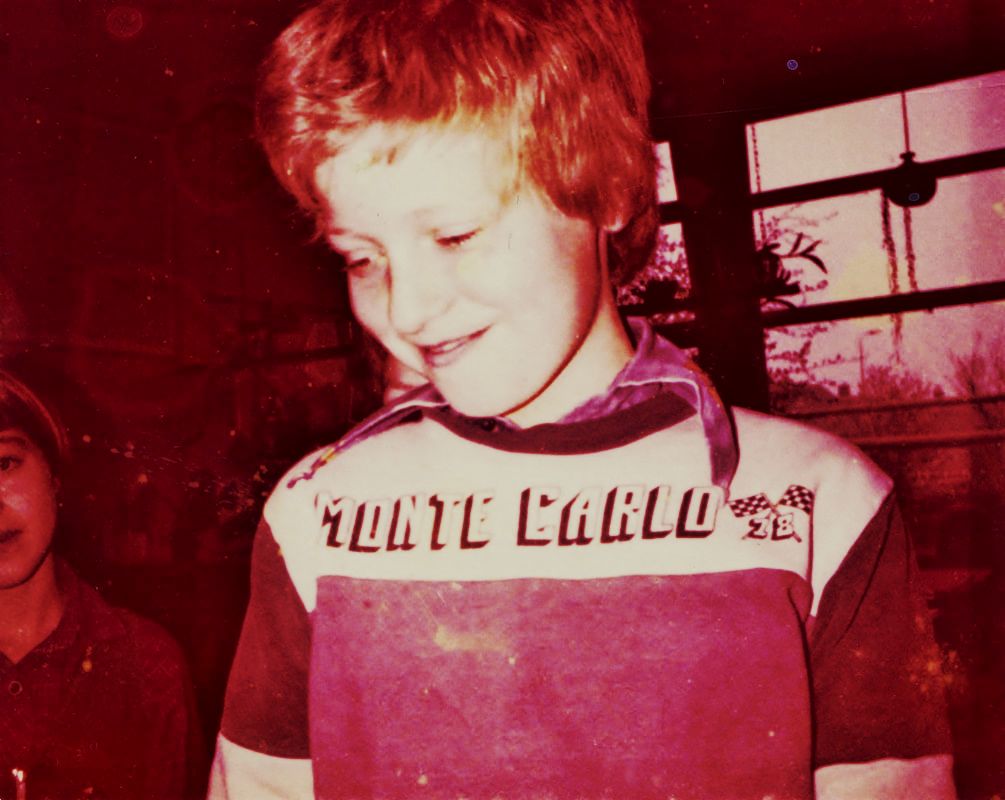

photo series my father made of me while I was playing and dreaming and finally became aware of him, around 1973

I often say that I was my best self as a boy.

By that, I do not mean that I do not like to be an adult, a father and a husband. What I mean by the boy as my best self is that therein lies my most honest and most fundamental nature. The childlike state, in which I was not yet responsible for my own needs - let alone for those of others - gives that nature an even freer (even more beautiful) shine. Especially the period before compulsory schooling has that free shine. Free, but dependent. Dependent on the care and love of my parents, and the family and friends around us.

Something of that dependency, I never lost. I sometimes believe that dismay is also a basic state for me. The upset that a child feels when he loses his mother in the supermarket (De Nieuwe Weme, in our village). Or when one grabbed the hand of a strange man in the crowd, and suddenly it turned out that this hand was not your father's (at the Sint Nicolaas parade). And finally, as a toddler, having to go to school on your own for the first time. I can still see how my mother had to catch me when I ran away from her behind the dining table, because I had to put on my shoes to go to school.

The dismay that later turned out to be existential, when I heard that my grandmother was going to die, and she really (really!) did...

But the boy is so fundamental to me because of the free time I had to play. I was already aware as a boy how wonderful it was to be able to play - but above all, that this entailed a special state, distinct from the ordinary state of being. Listening to or reading stories was an extension of this. Drawing and 'making' (tinkering was not a derogatory word to me then), and watching shows on television or at school (the puppet show). or singing a song, could also bring this about.

So as a boy, I loved being able and be allowed to play, and I was aware that this brought with it a special state of being and that it required a special effort to reach that state. In the game I was away for a moment, removed from the ordinary world. I was there, in the game, no longer aware of what was happening around me. Everything disappeared, and only the game was real. I remember well and vividly the regret I felt when, towards puberty, I discovered that it was becoming more difficult to reach that state. In much more than one way, I was a true Peter Pan. I fiercely resisted becoming an adult.

The boy plays. And in the game he discovers that he is part of a world. There is not only that house, that neighbourhood and that, his own family. There is a whole world, where things can also be very different from where he is. The possibilities meant, besides fear (I saw on television that there had been an earthquake in Italy that had destroyed everything), especially joy, energy and hope. If only I could be like Mark of G-force. Who knows, I might well become him.

But these examples are coming from the slightly older boy. The little boy at home was playing with some tools from his father's toolbox, and saw in them a large fish that wanted to catch other fish with its grabbing mouth. Or that could talk, and went out with other tool creatures, to find a place to live.

The imagination is the basis of all thinking and all wanting to know and understand. It is the most honest and fundamental faculty for me, and also the ability that makes it possible to do art. Because just as playing is something that has to be done, so too is art something that has to be done. It is not about the residue of that happening, although that makes a wonderful memory of that happening possible, and can in itself make it happen again - by imagination. And it can go further. Become another game. A continuation of what had already happened and already was discovered.

The boy already knew that this was his role in life. It was his favourite thing to do. And he could do it so incredibly well. I have always stayed with that boy and I always look for him. He is my most fundamental and honest self.

I didn't have to become him, because I was him already.

By that, I do not mean that I do not like to be an adult, a father and a husband. What I mean by the boy as my best self is that therein lies my most honest and most fundamental nature. The childlike state, in which I was not yet responsible for my own needs - let alone for those of others - gives that nature an even freer (even more beautiful) shine. Especially the period before compulsory schooling has that free shine. Free, but dependent. Dependent on the care and love of my parents, and the family and friends around us.

Something of that dependency, I never lost. I sometimes believe that dismay is also a basic state for me. The upset that a child feels when he loses his mother in the supermarket (De Nieuwe Weme, in our village). Or when one grabbed the hand of a strange man in the crowd, and suddenly it turned out that this hand was not your father's (at the Sint Nicolaas parade). And finally, as a toddler, having to go to school on your own for the first time. I can still see how my mother had to catch me when I ran away from her behind the dining table, because I had to put on my shoes to go to school.

The dismay that later turned out to be existential, when I heard that my grandmother was going to die, and she really (really!) did...

But the boy is so fundamental to me because of the free time I had to play. I was already aware as a boy how wonderful it was to be able to play - but above all, that this entailed a special state, distinct from the ordinary state of being. Listening to or reading stories was an extension of this. Drawing and 'making' (tinkering was not a derogatory word to me then), and watching shows on television or at school (the puppet show). or singing a song, could also bring this about.

So as a boy, I loved being able and be allowed to play, and I was aware that this brought with it a special state of being and that it required a special effort to reach that state. In the game I was away for a moment, removed from the ordinary world. I was there, in the game, no longer aware of what was happening around me. Everything disappeared, and only the game was real. I remember well and vividly the regret I felt when, towards puberty, I discovered that it was becoming more difficult to reach that state. In much more than one way, I was a true Peter Pan. I fiercely resisted becoming an adult.

The boy plays. And in the game he discovers that he is part of a world. There is not only that house, that neighbourhood and that, his own family. There is a whole world, where things can also be very different from where he is. The possibilities meant, besides fear (I saw on television that there had been an earthquake in Italy that had destroyed everything), especially joy, energy and hope. If only I could be like Mark of G-force. Who knows, I might well become him.

But these examples are coming from the slightly older boy. The little boy at home was playing with some tools from his father's toolbox, and saw in them a large fish that wanted to catch other fish with its grabbing mouth. Or that could talk, and went out with other tool creatures, to find a place to live.

The imagination is the basis of all thinking and all wanting to know and understand. It is the most honest and fundamental faculty for me, and also the ability that makes it possible to do art. Because just as playing is something that has to be done, so too is art something that has to be done. It is not about the residue of that happening, although that makes a wonderful memory of that happening possible, and can in itself make it happen again - by imagination. And it can go further. Become another game. A continuation of what had already happened and already was discovered.

The boy already knew that this was his role in life. It was his favourite thing to do. And he could do it so incredibly well. I have always stayed with that boy and I always look for him. He is my most fundamental and honest self.

I didn't have to become him, because I was him already.

|

TK 10-12-2021

|

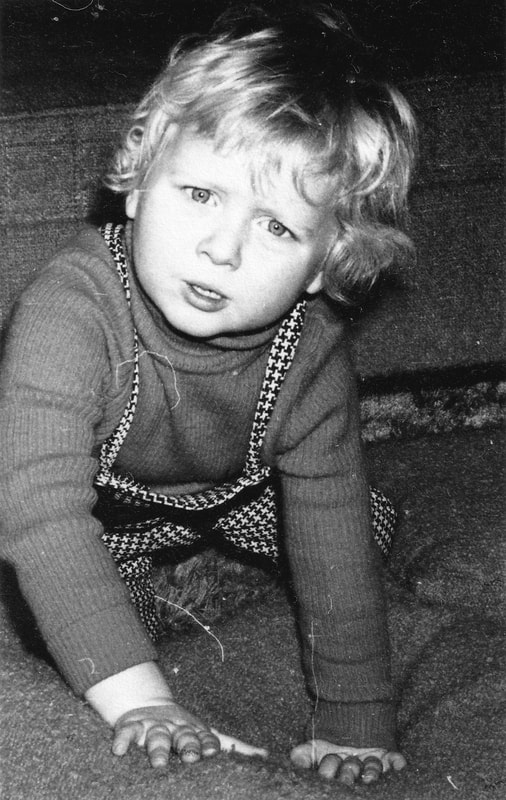

A photo for a Christmas card, that my father made of my brother and me, in 1975. Standerstraat 38.

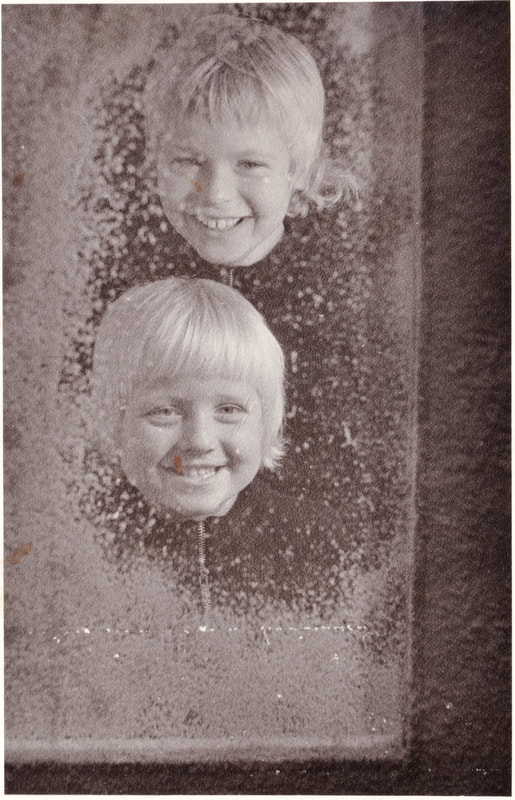

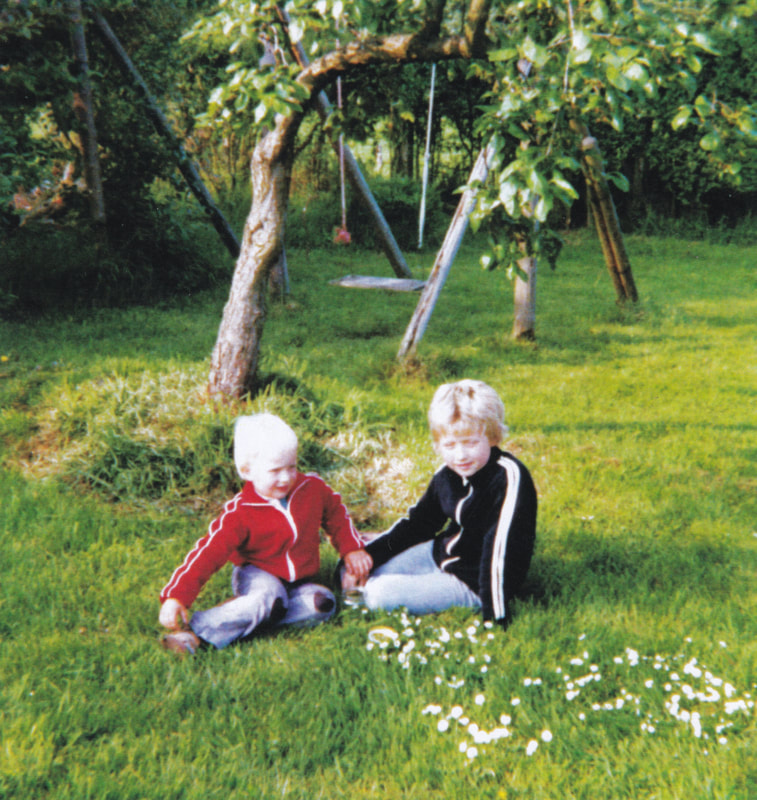

In the garden of my grandfather, with my younger brother in 1978, Lycklamaweg 17.

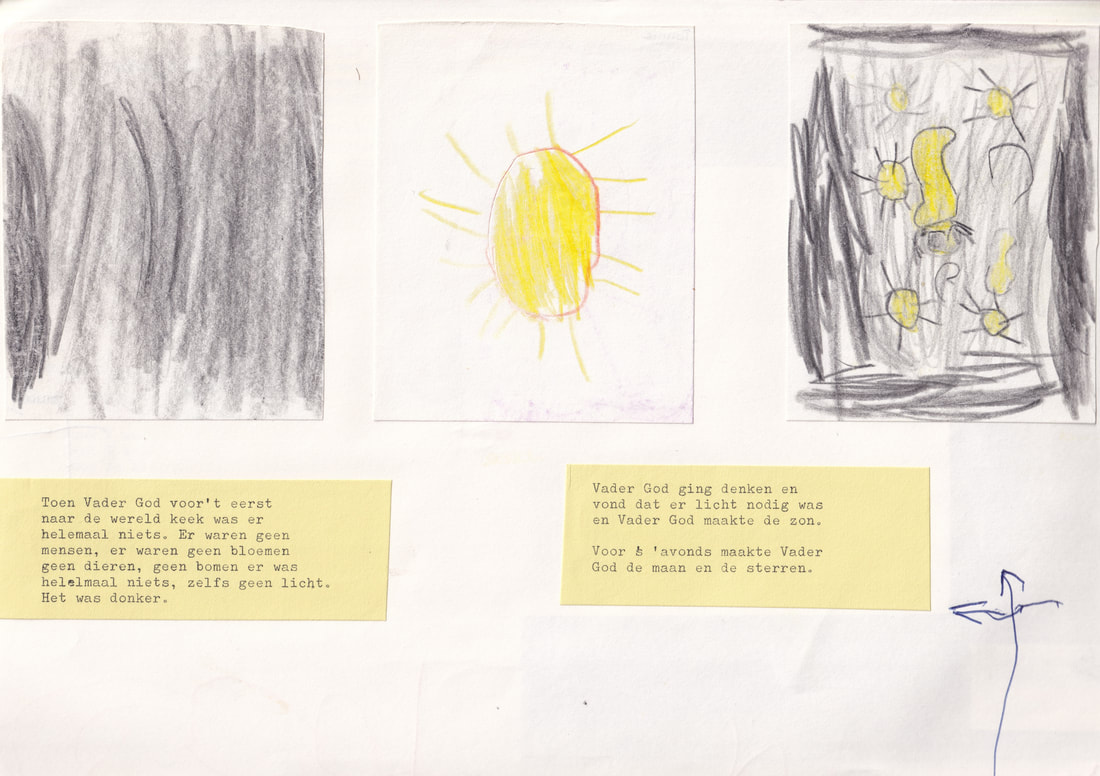

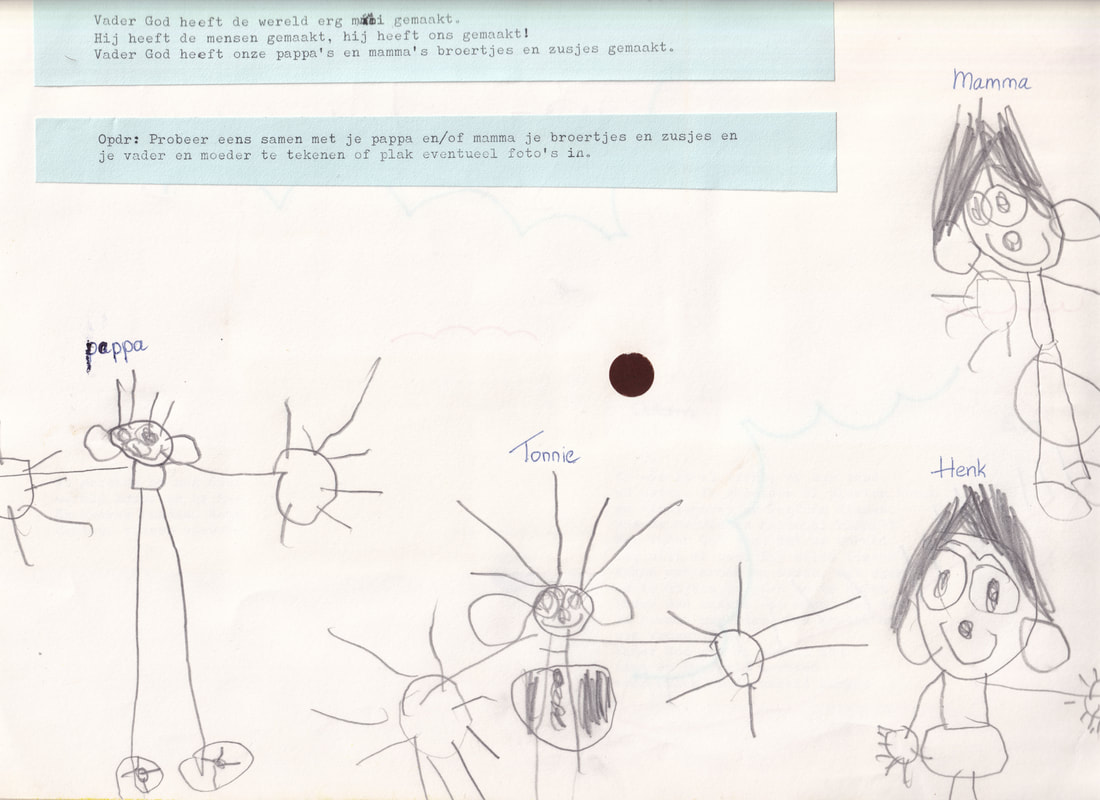

Pages from my catechesis workbook of nursery school, 1975. Below that my first writing from '76.

In the garden of my grandfather, with my younger brother in 1978, Lycklamaweg 17.

Pages from my catechesis workbook of nursery school, 1975. Below that my first writing from '76.

There is no training for the profession of 'artist', as if it were a trade that could be defined in terms of competences, skills and knowledge. An artist is not the same as a craftsman or a tradesman.

Only through study one can gain access to the practice of autonomous and contemporary art. By learning, and by learning to understand, what standards of excellence, what values and what goals are pursued in it. By learning to know and understand those standards, values and goals, and by relating to them in ones own work, one takes part in the discourse that constantly develops this practice. In this way, one becomes part of the practice and becomes an artist.

Having a disposition for artisthood is not the same as having a 'talent' for it. There is no spiritual power that gives a person a 'talent', and perhaps also the task of multiplying this talent and making it 'bear fruit'. The common use of the biblical concept of 'talent' presupposes that magically, or in a spiritual sense, great talents exist, which by their nature - as if automatically - perform great works. It is the echo of the belief in the artist-genius of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Unlike 'talent', aptitude refers to the genetic properties that make an individual have a certain preference for certain behaviour (interest) and the ability to develop this behaviour (intelligence, motor skills).

As a boy, I had a penchant for everything that falls outside the everyday order. Everything that added to, and was separate from, the daily needs and goings on. I had no interest in knowing how a bicycle was put together, how a policeman controlled the traffic, how the farmer drove his tractor or how milk was produced and sold. I was interested in the stories that were told about it, in television programmes, in books and stories, in puppet plays, songs and music. As a boy, I had a penchant for anything that is categorised as 'art'.

In our village, the capital of a rural region in Friesland, there was no museum or concert hall. Only later, when I took art as an exam subject, at the age of seventeen, did I visit a museum for the first time (the Stedelijk Museum of Amsterdam). The main places in our village where art (in a broad sense) could be found were the church, the library, school and television.

My father was a teacher of Dutch Language and Literature and loved classical music. He also drew and made photographs or films. My mother read to us and made sure that we had books and magazines. My brothers and I had access to all kinds of books in the house. On Sundays there was the liturgy, with hymns or Gregorian chant (from the choir wherein my grandfather and father sang) and the readings from the Bible - in a large church building with stained-glass windows, paintings and sculptures.

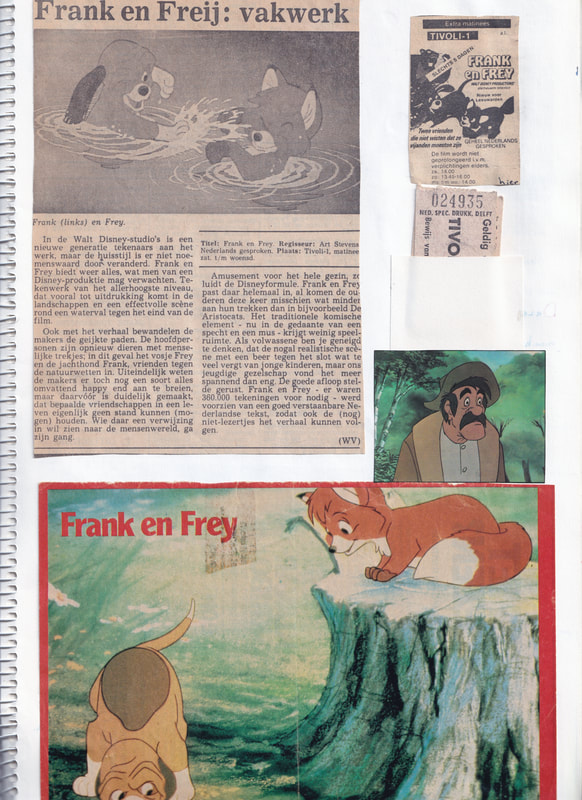

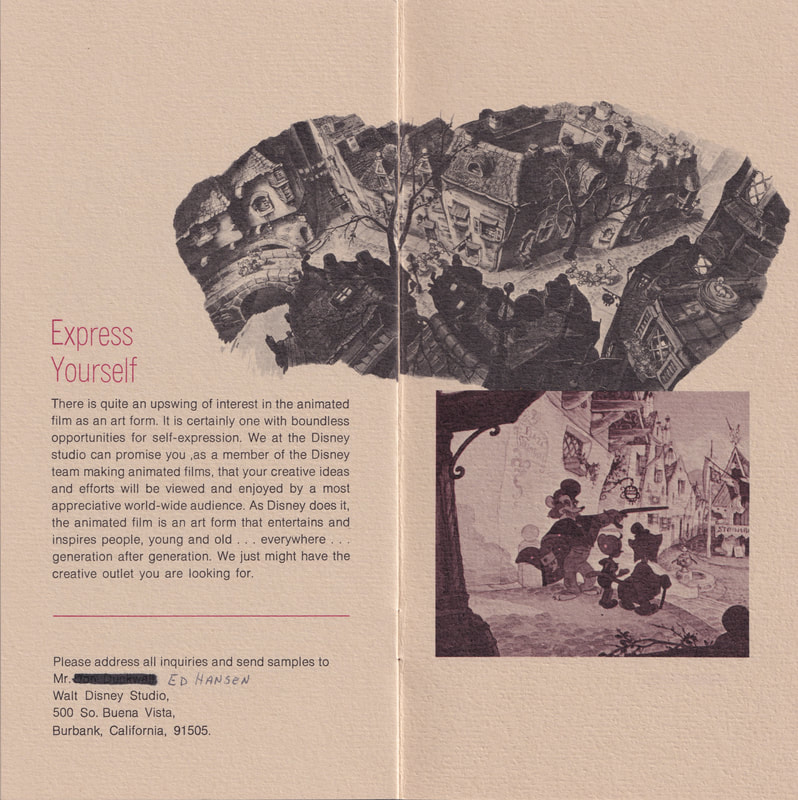

When I was ten years old, the Walt Disney Studio released 'the Fox and the Hound'. I was grabbed by it tremendously - both by the story of the impossible friendship and by its form and structure. I was able to see the film at the matinee in Leeuwarden. I studied how the film was made and did a talk about Walt Disney at school. For this I was allowed to borrow a book from a school friend: 'Walt Disney: from Mickey Mouse to Disneyland' (Christopher Finch, Landshoff Publishers, 1975). From studying this book, I learned to look at the practice of Walt Disney and his films in a studious and reflective way. I made the step from being an observer to being a 'maker'. With my best friend, I then made radio plays on his cassette recorder, a magazine about both the films of Walt Disney and about 'nature' - we also made our own cartoon characters for this, and our own (stop motion) animated films with my father's super 8 equipment.

Only through study one can gain access to the practice of autonomous and contemporary art. By learning, and by learning to understand, what standards of excellence, what values and what goals are pursued in it. By learning to know and understand those standards, values and goals, and by relating to them in ones own work, one takes part in the discourse that constantly develops this practice. In this way, one becomes part of the practice and becomes an artist.

Having a disposition for artisthood is not the same as having a 'talent' for it. There is no spiritual power that gives a person a 'talent', and perhaps also the task of multiplying this talent and making it 'bear fruit'. The common use of the biblical concept of 'talent' presupposes that magically, or in a spiritual sense, great talents exist, which by their nature - as if automatically - perform great works. It is the echo of the belief in the artist-genius of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Unlike 'talent', aptitude refers to the genetic properties that make an individual have a certain preference for certain behaviour (interest) and the ability to develop this behaviour (intelligence, motor skills).

As a boy, I had a penchant for everything that falls outside the everyday order. Everything that added to, and was separate from, the daily needs and goings on. I had no interest in knowing how a bicycle was put together, how a policeman controlled the traffic, how the farmer drove his tractor or how milk was produced and sold. I was interested in the stories that were told about it, in television programmes, in books and stories, in puppet plays, songs and music. As a boy, I had a penchant for anything that is categorised as 'art'.

In our village, the capital of a rural region in Friesland, there was no museum or concert hall. Only later, when I took art as an exam subject, at the age of seventeen, did I visit a museum for the first time (the Stedelijk Museum of Amsterdam). The main places in our village where art (in a broad sense) could be found were the church, the library, school and television.

My father was a teacher of Dutch Language and Literature and loved classical music. He also drew and made photographs or films. My mother read to us and made sure that we had books and magazines. My brothers and I had access to all kinds of books in the house. On Sundays there was the liturgy, with hymns or Gregorian chant (from the choir wherein my grandfather and father sang) and the readings from the Bible - in a large church building with stained-glass windows, paintings and sculptures.

When I was ten years old, the Walt Disney Studio released 'the Fox and the Hound'. I was grabbed by it tremendously - both by the story of the impossible friendship and by its form and structure. I was able to see the film at the matinee in Leeuwarden. I studied how the film was made and did a talk about Walt Disney at school. For this I was allowed to borrow a book from a school friend: 'Walt Disney: from Mickey Mouse to Disneyland' (Christopher Finch, Landshoff Publishers, 1975). From studying this book, I learned to look at the practice of Walt Disney and his films in a studious and reflective way. I made the step from being an observer to being a 'maker'. With my best friend, I then made radio plays on his cassette recorder, a magazine about both the films of Walt Disney and about 'nature' - we also made our own cartoon characters for this, and our own (stop motion) animated films with my father's super 8 equipment.

|

TK 17-12-2021

|

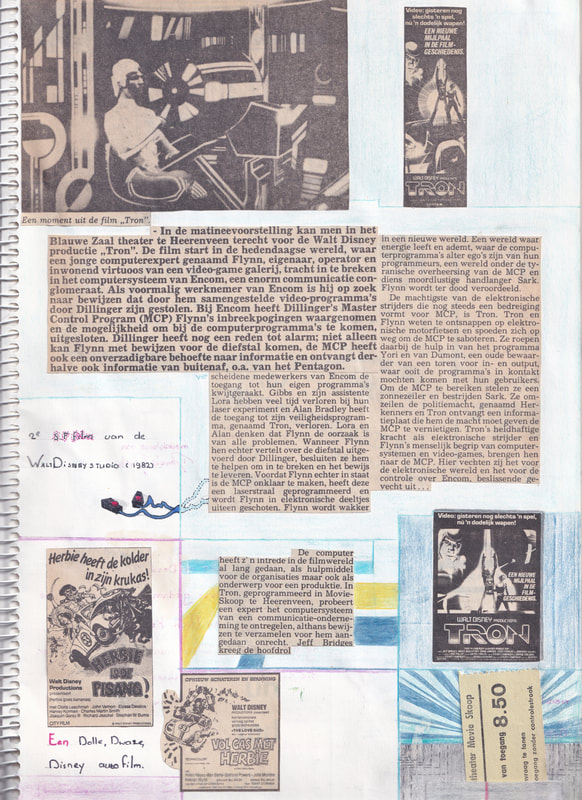

Some pages from a scrapbook that I kept, about films by Walt Disney, 1981 and 1982.

Where up to modern times, and for some perhaps to the present day, an artist was defined by her, his or their skill in the use of certain media - drawing and painting, graphics, sculpture, literature, dance, etcetera - which were seen as distinct 'disciplines' within art, this distinction and definition has become meaningless for a contemporary artist. As a contemporary artist, not as a historical demarcation but as a distinct mode of art practice, I have never seen myself as a 'painter', a 'photographer' or a 'graphic artist'. Artisthood to me, is not defined by skill and competence in the use of a medium - a medium like that where one works in. I look for my artisthood in the qualitative use of different media.

This does not mean that skill and competence have become irrelevant. I use the media I choose in a skilful and competent manner. If I didn't, I couldn't be a good artist. One has to know the material one chooses, and be able to use it in such a way that it does what it should and can do. The difference lies in the fact that the artistic aspect, that which makes your work a work of art, does not depend on a pre- (academic) standardized use of materials, but on the way in which the use of materials puts the work into effect as an art-work. A contemporary artist is therefore not bound to certain 'disciplines'. Although we still speak of 'visual' art (this may be the time to drop this identification), a contemporary visual artist can also work with text and language, with the body and body movements, with performative actions, and with theatrical interactions - in addition to painting, spatial work and time-based media, or other, traditionally identified 'visual' media. This openness is perceived by some as indefinable, and I will admit that no consensus has yet been reached among academics and among artists about the definition of the artfulness of works of art, but to me all of this is just as irrelevant as the delineation of artisthood by media use.

The origin of my view on contemporary artistry may have been partly shaped by my history as a child and teenager in a larger, Frisian rural village. Due to the lack of a direct access to autonomous art in my environment, as an artistically inclined child, I was dependent on the art that was found in Church, school, on television and in the library. And, as described here above, when I was ten years old, I became captivated by the animation films of Walt Disney. That may sound like a clearly defined discipline, animated film, but of course it wasn't so really. Disney's work had roots in folk culture, (youth) literature and the broad, contemporary culture - and branched out into various artistic roles or tasks. In the beginning, Disney did a lot by himself, together with a friend. But soon the complexity of his work developed into a variety of tasks, such as: directing, layout, backgrounds, music, voice acting, animation and story-board/screenplay writing, special effects and camera. Disney himself increasingly became the artist who set things in motion, monitored and steered the direction in which work developed.

As a boy I was so captivated and inspired by this that I also developed my artistic interests in various forms. I wrote books, made plays, animation films, radio plays, drawings and comic strips. I also took up photography and when I got the chance I also worked with spatial media or theatre sets. In short, my fantasy and interests could take shape in various forms and was not determined by discipline thinking or by a predetermined standard. In this way, art was immediately completely free and open for me, and in addition to being individual it also had a collaborative elaboration.

This does not mean that skill and competence have become irrelevant. I use the media I choose in a skilful and competent manner. If I didn't, I couldn't be a good artist. One has to know the material one chooses, and be able to use it in such a way that it does what it should and can do. The difference lies in the fact that the artistic aspect, that which makes your work a work of art, does not depend on a pre- (academic) standardized use of materials, but on the way in which the use of materials puts the work into effect as an art-work. A contemporary artist is therefore not bound to certain 'disciplines'. Although we still speak of 'visual' art (this may be the time to drop this identification), a contemporary visual artist can also work with text and language, with the body and body movements, with performative actions, and with theatrical interactions - in addition to painting, spatial work and time-based media, or other, traditionally identified 'visual' media. This openness is perceived by some as indefinable, and I will admit that no consensus has yet been reached among academics and among artists about the definition of the artfulness of works of art, but to me all of this is just as irrelevant as the delineation of artisthood by media use.

The origin of my view on contemporary artistry may have been partly shaped by my history as a child and teenager in a larger, Frisian rural village. Due to the lack of a direct access to autonomous art in my environment, as an artistically inclined child, I was dependent on the art that was found in Church, school, on television and in the library. And, as described here above, when I was ten years old, I became captivated by the animation films of Walt Disney. That may sound like a clearly defined discipline, animated film, but of course it wasn't so really. Disney's work had roots in folk culture, (youth) literature and the broad, contemporary culture - and branched out into various artistic roles or tasks. In the beginning, Disney did a lot by himself, together with a friend. But soon the complexity of his work developed into a variety of tasks, such as: directing, layout, backgrounds, music, voice acting, animation and story-board/screenplay writing, special effects and camera. Disney himself increasingly became the artist who set things in motion, monitored and steered the direction in which work developed.

As a boy I was so captivated and inspired by this that I also developed my artistic interests in various forms. I wrote books, made plays, animation films, radio plays, drawings and comic strips. I also took up photography and when I got the chance I also worked with spatial media or theatre sets. In short, my fantasy and interests could take shape in various forms and was not determined by discipline thinking or by a predetermined standard. In this way, art was immediately completely free and open for me, and in addition to being individual it also had a collaborative elaboration.

|

TK 27-12-2021

|

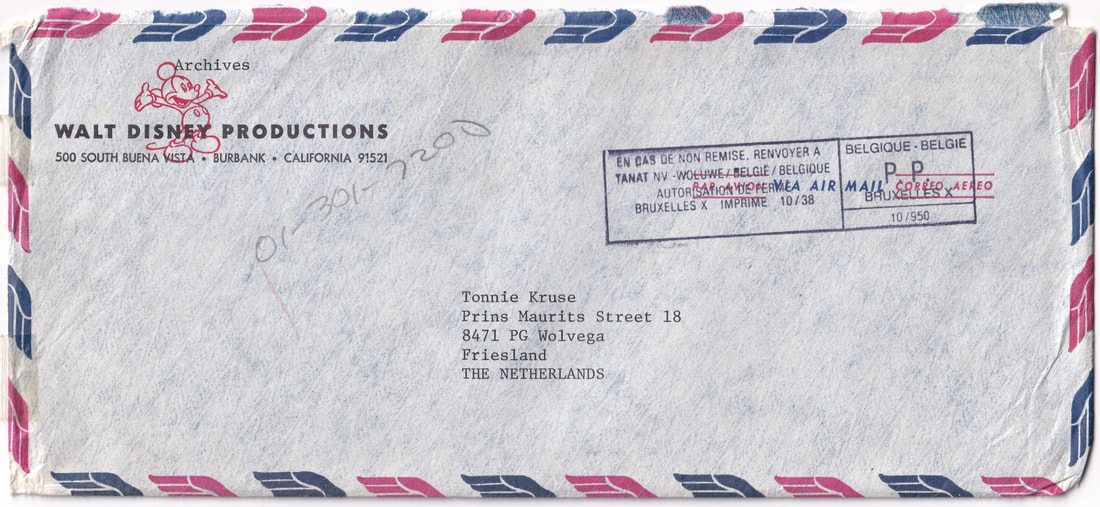

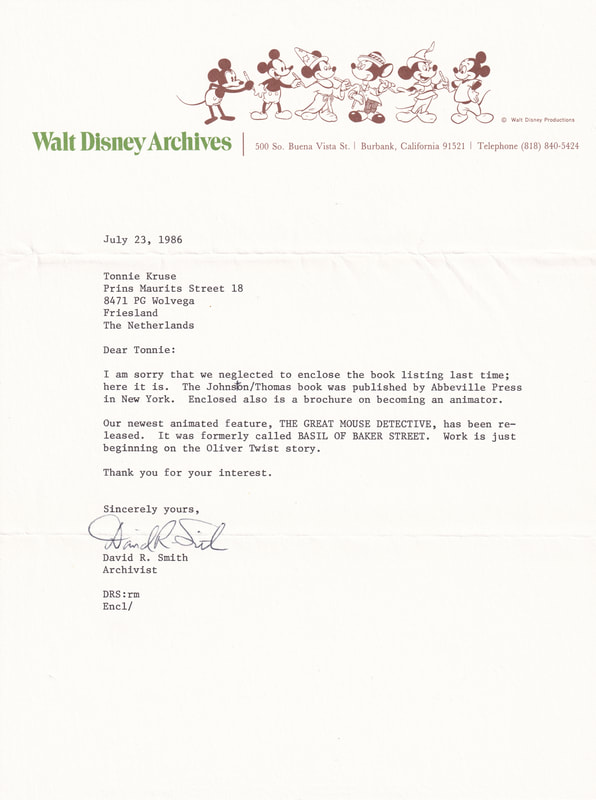

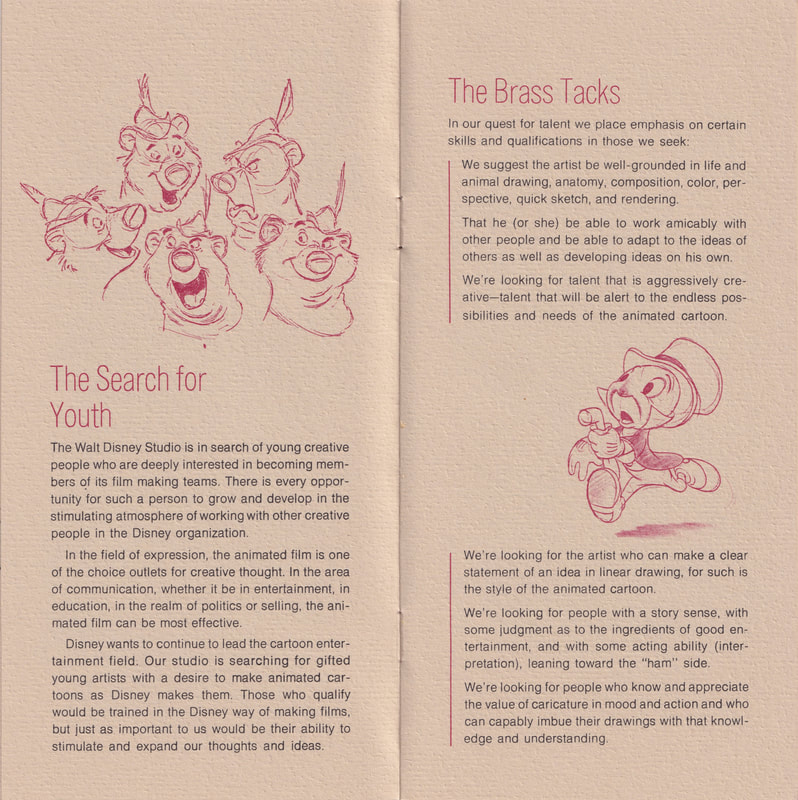

Parts of an answer I received to my question about how to come to work at Walt Disney's animation studio, 1986.

Puberty is a rite of passage. For me, it was a period of a forced goodbye to, and the transformation of the things that defined me. Indeed, in addition to the physical changes of growing up, the things I did with my friends also changed. I felt I was forced to leave my loves behind. New loves took their place. For me, as a true Peter Pan, these new loves were marked with the pain of those lost loves. I intend the radio plays, the newspapers, the animated films that I made with my best friend. In my heart, I would have preferred to develop these further. I resisted the breaking of my voice, tried to keep it at its boyhood pitch, and shaved the new leg hair from my legs. A hopeless resistance that, of course, I eventually had to give up.

It was the time of the so-called second wave of the punk movement from the UK, the 'new wave'. My friend and I listened endlessly to 'The Unforgetable Fire' (U2) and 'Curiosity (Killing the Cat)' (the Cure) on his Radio-Cassette recorder. Later, other records were added: 'The Scream' (Siouxsie and the Banshees), 'The Queen is Dead' (the Smiths), 'Heaven Up Here' (Echo and the Bunnymen) and 'Substance' (New Order). But our classmates, my friend and I were in different high schools, listened to the main stream pop of Hilversum 3. There it was Madonna, Prince, Wham and Kylie Minogue that were appreciated. It was a time with distinct youth subcultures and there were only a few who understood why I appreciated this punk new wave music, that was barely heard on the radio. It's probably a universal characteristic of adolescents and teenagers, but me and us, I and we felt lonely and, above all, misunderstood. A sense of life that we somehow recognized in the lyrics of the bands we appreciated. I called it melancholy, or the feeling of a sad happiness. The loss of my boyhood was definitely part of that. But it was also about what Morrissey so aptly described on 'Viva Hate':

Ordinary boys / Happy knowing nothing / Happy being no one but themselves / Ordinary girls / Supermarket clothes / Who think it's very clever to be cruel to you / For you were so different / You stood all alone / And you knew that it had to be so / Avoiding ordinary boys / Happy going nowhere / Just around here in their rattling cars / Ordinary girls / Never seeing further than the cold, small streets that trap them / But you were so different / You had to say you know / When those empty fools tried to change you / And claim you / For the lair of their ordinary world / Where they feel so lucky / So lucky / So lucky / With their lives laid out before them / They're lucky / So lucky / So lucky / So lucky / So

That my dear grandmother became seriously ill and had to die, also happened during that time. The reality of our ultimate finitude was a harsh shock, that I never really got over.

There were several aspects of this punk music that appealed to me. The first, I think, was the DIY (Do It Yourself) mentality. People were creative with the resources they had at their disposal. People didn't let lack of knowledge of music theory or skills on instruments hinder them. And so 'tracks' were created that were different from main stream pop and rock, and thus unexpected and surprising. For example, I was very charmed by 'If I Die I Die' (Virgin Prunes) and 'Half Mute' (Tuxedomoon). Song structures hardly have any part on these records. Another aspect that appealed to me was the care for the visual. For example, the bands we listened to had created interesting personas in their performances and music videos. They played with exaggeration, theatrical effects and narrative elements. 'The Caterpillar' by video director Tim Pope was mostly funny, but with an engaging disruption of the clownish, which is hard to define. In 'Since Yesterday,' Pope plays with the stop-motion trickery reminiscent of the 'Alice's Wonderland' series from the 1920s. Punk also developed a second branch during this period, called hardcore. But that dumb, often rather standard and mostly unimaginative ranting on electric guitars usually bored me thoroughly.

One aspect of that time, which is no longer understood by younger generations, was the scarcity of access to media. It could really take months before one heard about a record, let alone be able to buy one, or before you got to see a video. Many clips we didn't see at all, until years later, once we had MTV on the cable in our student dorms. There wasn't much media in the early 1980s, television had just two national channels and the radio was dominated by main stream pop. So, whatever music you had got hold of was treasured and 'played to death', so to speak. Many of the records or cassette tapes we had, I can still sing from heart. As an info source we bought the English Melodymaker and NME.

It was the time of the so-called second wave of the punk movement from the UK, the 'new wave'. My friend and I listened endlessly to 'The Unforgetable Fire' (U2) and 'Curiosity (Killing the Cat)' (the Cure) on his Radio-Cassette recorder. Later, other records were added: 'The Scream' (Siouxsie and the Banshees), 'The Queen is Dead' (the Smiths), 'Heaven Up Here' (Echo and the Bunnymen) and 'Substance' (New Order). But our classmates, my friend and I were in different high schools, listened to the main stream pop of Hilversum 3. There it was Madonna, Prince, Wham and Kylie Minogue that were appreciated. It was a time with distinct youth subcultures and there were only a few who understood why I appreciated this punk new wave music, that was barely heard on the radio. It's probably a universal characteristic of adolescents and teenagers, but me and us, I and we felt lonely and, above all, misunderstood. A sense of life that we somehow recognized in the lyrics of the bands we appreciated. I called it melancholy, or the feeling of a sad happiness. The loss of my boyhood was definitely part of that. But it was also about what Morrissey so aptly described on 'Viva Hate':

Ordinary boys / Happy knowing nothing / Happy being no one but themselves / Ordinary girls / Supermarket clothes / Who think it's very clever to be cruel to you / For you were so different / You stood all alone / And you knew that it had to be so / Avoiding ordinary boys / Happy going nowhere / Just around here in their rattling cars / Ordinary girls / Never seeing further than the cold, small streets that trap them / But you were so different / You had to say you know / When those empty fools tried to change you / And claim you / For the lair of their ordinary world / Where they feel so lucky / So lucky / So lucky / With their lives laid out before them / They're lucky / So lucky / So lucky / So lucky / So

That my dear grandmother became seriously ill and had to die, also happened during that time. The reality of our ultimate finitude was a harsh shock, that I never really got over.

There were several aspects of this punk music that appealed to me. The first, I think, was the DIY (Do It Yourself) mentality. People were creative with the resources they had at their disposal. People didn't let lack of knowledge of music theory or skills on instruments hinder them. And so 'tracks' were created that were different from main stream pop and rock, and thus unexpected and surprising. For example, I was very charmed by 'If I Die I Die' (Virgin Prunes) and 'Half Mute' (Tuxedomoon). Song structures hardly have any part on these records. Another aspect that appealed to me was the care for the visual. For example, the bands we listened to had created interesting personas in their performances and music videos. They played with exaggeration, theatrical effects and narrative elements. 'The Caterpillar' by video director Tim Pope was mostly funny, but with an engaging disruption of the clownish, which is hard to define. In 'Since Yesterday,' Pope plays with the stop-motion trickery reminiscent of the 'Alice's Wonderland' series from the 1920s. Punk also developed a second branch during this period, called hardcore. But that dumb, often rather standard and mostly unimaginative ranting on electric guitars usually bored me thoroughly.

One aspect of that time, which is no longer understood by younger generations, was the scarcity of access to media. It could really take months before one heard about a record, let alone be able to buy one, or before you got to see a video. Many clips we didn't see at all, until years later, once we had MTV on the cable in our student dorms. There wasn't much media in the early 1980s, television had just two national channels and the radio was dominated by main stream pop. So, whatever music you had got hold of was treasured and 'played to death', so to speak. Many of the records or cassette tapes we had, I can still sing from heart. As an info source we bought the English Melodymaker and NME.

|

TK 24-01-2022

|

The view from my room; on the Dracht in Heerenveen; and in the Open Air Museum Arnhem with Teen Tour NS, 1987

In the second half of the eighties, my friend and I started our own band, for which I wrote. Sometimes on my own, sometimes together with my friend. We asked another friend that we knew from our elementary school to play the drums. I played guitar and did the vocals. I named the band after a book by a writer that I enjoyed reading in that period, J.M.A. (Maarten) Biesheuvel: De verpletterende werkelijkheid - so: Crashing Reality.

My interest in doing pop music came from the possibilities it offered to combine different forms. It combined text, sound and music, and divergent 'visual' forms: photo, video and performance. I found the blending of the artlike and the real interesting. The artist became a persona, a character - the artist - who related in an unclear way to the artist as a real person. As a persona, I could explore all sorts of positions that I would not occupy or possess as a human being.

I found pop music as a branch of the entertainment industry totally uninteresting and rather boring. I also hated going on stage as myself. I wasn't looking for that kind of status. For me, it was purely about the possibilities of mixing and combining artistic forms, and about the cooperation in that area. In my work, I enjoy having my own ideas crossed and supplemented by others. It fascinates me that my work is and remains even more unexpected by working together, ideas are added that I did not form myself. That surprises and opens possibilities and new perspectives. For good reason, I see my artisthood as my participation in a shared practice, not as something that belongs to me alone.

During and shortly after my studies of autonomous art, I also worked from this perspective on 'pop'. On this website, in the portfolio, I have made some audio recordings from that period accessible. The film 'Moonopoly' is also a result of this mixing of forms. Ultimately, the vocabulary of pop music proved to be too limited for me. I am much more interested in developing forms - including the musical form, and serious music is infinitely more complex than any DIY form of doing music. Therefore, I am currently much more interested in collaborating with trained composers than in working on music myself, untrained.

My interest in doing pop music came from the possibilities it offered to combine different forms. It combined text, sound and music, and divergent 'visual' forms: photo, video and performance. I found the blending of the artlike and the real interesting. The artist became a persona, a character - the artist - who related in an unclear way to the artist as a real person. As a persona, I could explore all sorts of positions that I would not occupy or possess as a human being.

I found pop music as a branch of the entertainment industry totally uninteresting and rather boring. I also hated going on stage as myself. I wasn't looking for that kind of status. For me, it was purely about the possibilities of mixing and combining artistic forms, and about the cooperation in that area. In my work, I enjoy having my own ideas crossed and supplemented by others. It fascinates me that my work is and remains even more unexpected by working together, ideas are added that I did not form myself. That surprises and opens possibilities and new perspectives. For good reason, I see my artisthood as my participation in a shared practice, not as something that belongs to me alone.

During and shortly after my studies of autonomous art, I also worked from this perspective on 'pop'. On this website, in the portfolio, I have made some audio recordings from that period accessible. The film 'Moonopoly' is also a result of this mixing of forms. Ultimately, the vocabulary of pop music proved to be too limited for me. I am much more interested in developing forms - including the musical form, and serious music is infinitely more complex than any DIY form of doing music. Therefore, I am currently much more interested in collaborating with trained composers than in working on music myself, untrained.

|

TK 2-2-2022

|

Practising with my band Crashing Reality in the cold store of Hoofdstraat West 2, 1989.

My red-eared turtle in the backyard, Prins Mauritsstraat 18, 1989; Passport photo, 1990.

My red-eared turtle in the backyard, Prins Mauritsstraat 18, 1989; Passport photo, 1990.

Being an artist is a precarious state in many respects. It is out of order in several ways: it is not a clearly defined craft (a trade) that is learned and then practiced in order to earn a living. Professions that are, have a clear place in the economic and social order. As an artist one stands outside of both orders, and one is repeatedly asked to justify oneself: what do you do - and why do you do that?

My parents saw this problem in being an artist and therefore suggested that I would train to become a primary school teacher after my secondary education. As a teachet I would be able to shape my calling as a hobby in my spare time. As a seventeen-year-old I agreed to that, aware of my great uncertainty about how the world worked and what place I could have in it. In the round of introductions, on the open day of the Normal School, we as prospective students were asked why we chose to become a primary education teacher. In all honesty, I said: because my parents thought it best.

Although I really enjoyed being in a Normal School class with a high percentage of women, and although I also loved reading to, and playing with the children at my internship schools, and giving drawing and history lessons - or taking them out to study nature, I switched after a few years to a study of autonomous art in Enschede. I had learned that one cannot deny oneself. Who one is must fit what one does, otherwise one will be frustrated all the time.

But unlike my brothers, who ended up with engineering companies through academic studies, I lacked such structures that enable one to move onto a position somewhere, through study and further training. Fortunately, my brothers therefore never - or hardly ever, had to rely on welfare, or had to deal with searches for ways to provide for themselves. But I have worked in the hospitality industry, did construction work and divergent other side jobs after graduating. Always from, and returning to a startingposition of welfare. Annoying, unhealthy and bmost of all: unskilled work. There is no function or position in our social order for an autonomous artist, so I immediately looked for a gallery after graduation. Because selling works of art is the only way by which an autonomous artist can acquire a place within the social and economic order.

But a commercial enterprise clashes with the nature of autonomous artisthood, which is based on very different values and goals than an entrepreneurship that ultimately strives to earn an income by its trade. After my first solo in Haarlem I immediately got a depression and gradually slipped into a burnout. The money one earns from selling ones work turned out to be just plain money that just got spent - it added nothing substantial to my work as an artist. Contacts with customers went through the gallerist and therefore did not contribute anything to my work either. The informal structures with colleagues that I had at the time, as a young man and aspiring artist, turned out to be too weak to give meaning to my work, based on a shared practice. I also lacked mentors and the means for further study.

Even now, none of my colleagues actually earn a full income from the sale of their work. The teachers I had at the Academy did not earn their income from commerce as well, but from their teaching positions and from additional status-related positions, such as committee work. Even colleagues who have a certain status in the commercial art world and the institutional art world, do not earn a full income from the sale of their work. Think about how much work one would have to sell per month, and at what prices, to earn a reasonable income after deducting fixed costs and expenses. And just look at how many presentations autonomous artists have per year. It then will quickly become clear, that earning an income from sales is only possible at super high unit prices, or by producing a lot of the same, until the market is saturated.

None of this adds anything to the work one does as an artist and why one does it. Work that revolves around acquiring knowledge and insights in areas that usually have no direct practical or economic use. Work that is often difficult to describe to people who know nothing about such a practice, a practice where high ethical and intellectual values apply to. It is therefore actually bizarre that in the Netherlands - in contrast to other countries - the study of autonomous art is classified as 'Higher Professional Education' and not as part of the Humanities Faculties of Universities.

An existence outside the economic and social order means an existence on the fringes of these orders. This has all kinds of consequences for both the person and their work. It has effects on ones health, on ones possibilities and on ones lifespan and vulnerability in divergent areas. For me it has always been a quest to find a balance between work and life, and how to be able to still do what my work asks for. Only by taking a teaching position in secondary education it became possible for me to start a family and buy a house. But this inevitably compromised my artisthood. I am now working fully independent again, as an artist and art theorist. As a member of the board of the artists trade union, I have commited myself for some time to the social dialogue between trade unions, interest groups and governments. So, I know from studies and contacts that autonomous artists in our country (and beyond) often do not have a family or a house of their own, and self-finance their practice with part-time jobs and furthermore with sporadic sales, sponsorship, and honorary positions (often just for expense allowances). The better off artists have their own money (through inheritance) or a working partner - the only ways to rise as an autonomous artist on the social ladder and gain a place in the social order, other than achieving great successes in the commercial art world (which is only is reserved for the less than 1%, and of which it must be questionable whether such a thing can actually be seriously aspired to).

Artisthood is out of all order in our times. I have learned to embrace this position as an outsider and stranger. It is a political act to step outside the order, because by doing so that order is questioned.

But freedom is expensive for the autonomous artist.

My parents saw this problem in being an artist and therefore suggested that I would train to become a primary school teacher after my secondary education. As a teachet I would be able to shape my calling as a hobby in my spare time. As a seventeen-year-old I agreed to that, aware of my great uncertainty about how the world worked and what place I could have in it. In the round of introductions, on the open day of the Normal School, we as prospective students were asked why we chose to become a primary education teacher. In all honesty, I said: because my parents thought it best.

Although I really enjoyed being in a Normal School class with a high percentage of women, and although I also loved reading to, and playing with the children at my internship schools, and giving drawing and history lessons - or taking them out to study nature, I switched after a few years to a study of autonomous art in Enschede. I had learned that one cannot deny oneself. Who one is must fit what one does, otherwise one will be frustrated all the time.

But unlike my brothers, who ended up with engineering companies through academic studies, I lacked such structures that enable one to move onto a position somewhere, through study and further training. Fortunately, my brothers therefore never - or hardly ever, had to rely on welfare, or had to deal with searches for ways to provide for themselves. But I have worked in the hospitality industry, did construction work and divergent other side jobs after graduating. Always from, and returning to a startingposition of welfare. Annoying, unhealthy and bmost of all: unskilled work. There is no function or position in our social order for an autonomous artist, so I immediately looked for a gallery after graduation. Because selling works of art is the only way by which an autonomous artist can acquire a place within the social and economic order.

But a commercial enterprise clashes with the nature of autonomous artisthood, which is based on very different values and goals than an entrepreneurship that ultimately strives to earn an income by its trade. After my first solo in Haarlem I immediately got a depression and gradually slipped into a burnout. The money one earns from selling ones work turned out to be just plain money that just got spent - it added nothing substantial to my work as an artist. Contacts with customers went through the gallerist and therefore did not contribute anything to my work either. The informal structures with colleagues that I had at the time, as a young man and aspiring artist, turned out to be too weak to give meaning to my work, based on a shared practice. I also lacked mentors and the means for further study.

Even now, none of my colleagues actually earn a full income from the sale of their work. The teachers I had at the Academy did not earn their income from commerce as well, but from their teaching positions and from additional status-related positions, such as committee work. Even colleagues who have a certain status in the commercial art world and the institutional art world, do not earn a full income from the sale of their work. Think about how much work one would have to sell per month, and at what prices, to earn a reasonable income after deducting fixed costs and expenses. And just look at how many presentations autonomous artists have per year. It then will quickly become clear, that earning an income from sales is only possible at super high unit prices, or by producing a lot of the same, until the market is saturated.

None of this adds anything to the work one does as an artist and why one does it. Work that revolves around acquiring knowledge and insights in areas that usually have no direct practical or economic use. Work that is often difficult to describe to people who know nothing about such a practice, a practice where high ethical and intellectual values apply to. It is therefore actually bizarre that in the Netherlands - in contrast to other countries - the study of autonomous art is classified as 'Higher Professional Education' and not as part of the Humanities Faculties of Universities.

An existence outside the economic and social order means an existence on the fringes of these orders. This has all kinds of consequences for both the person and their work. It has effects on ones health, on ones possibilities and on ones lifespan and vulnerability in divergent areas. For me it has always been a quest to find a balance between work and life, and how to be able to still do what my work asks for. Only by taking a teaching position in secondary education it became possible for me to start a family and buy a house. But this inevitably compromised my artisthood. I am now working fully independent again, as an artist and art theorist. As a member of the board of the artists trade union, I have commited myself for some time to the social dialogue between trade unions, interest groups and governments. So, I know from studies and contacts that autonomous artists in our country (and beyond) often do not have a family or a house of their own, and self-finance their practice with part-time jobs and furthermore with sporadic sales, sponsorship, and honorary positions (often just for expense allowances). The better off artists have their own money (through inheritance) or a working partner - the only ways to rise as an autonomous artist on the social ladder and gain a place in the social order, other than achieving great successes in the commercial art world (which is only is reserved for the less than 1%, and of which it must be questionable whether such a thing can actually be seriously aspired to).

Artisthood is out of all order in our times. I have learned to embrace this position as an outsider and stranger. It is a political act to step outside the order, because by doing so that order is questioned.

But freedom is expensive for the autonomous artist.

|

TK 28-02-2022

|

Exchange week in Bruges, with the Catholic Normal School, 1990.

Today, we still speak of different forms of (autonomous) art. We distinguish literary art, choreographic art, musical art and visual art. The first form is limited to language use, the second to dance forms, the third to music-compositional forms. The latter form should then be limited to 'visual' forms: images. The term image, comes from the Latin word 'imago', which means imitation or representation. In some cases it can also be an example of a general category - so not an imitation of an individual case or person, but an example of a category.

Art theory has long since developed beyond the concept of art as mimesis via Heidegger, Arendt, Ricoeur and Gadamer. The theorists mentioned here, have sufficiently demonstrated that a work of art is not a doubling of reality (mimesis), but an increase. A work of art adds something that wasn't there before. Of course, it thereby puts that which is (already) in a specific relationship through its own, inalienable properties. By that I mean: the work of art is not a mere form, but is related in various, meaningful ways to the world around it - the world that preceded it, from which it originated and into which it enters.

What therefore remains of the 'visual' in visual art is the image as an example of more general categories. The 'image' says something about what it is or can be an image of. In the first place of himself, but, as Ricoeur so aptly put it: “In my opinion, all expressions are inevitably about something.” (Paul Ricoeur, Tekst en Meaning, Ambo, Baarn, 1991, p. 98) That 'something' is subsequently: the 'world' and being in the world. The latter means: how (it is or can be) to exist between everything that is and what we can know and think about that. But also, says Ricoeur: “besides the non-showing but still descriptive references, also the non-showing and non-referring descriptions.” (Work cited, same page) A 'world' is therefore something that is created through, with and in the expressions of people. People from now and before. An ongoing project.

But with this we are again removed from the specificity of the visual of visual art. The visual arts, in this new understanding, can no longer be identified with the term 'image' or 'visual'. In contemporary (visual) art we can now see that artists no longer limit themselves to what was previously and traditionally understood as the 'visual' disciplines or media: painting and drawing, sculptural or spatial art, and the new media of film, video, 'digital' forms and installation art. Contemporary artists work just as well with language, with movement, and with sound. The distinctive character of the 'visual' in visual art has been lost. The other art forms are just as 'visual' - in the sense of relating to 'seeing' as the development of insights - as the visual arts are, and vice versa.

Although the views of Ricoeur and the other theorists mentioned above, were largely articulated before the 1990s, they were not taught or discussed at the Academy where I studied. I also wonder who of the current professors and teachers at the various Academies for Visual Arts today know, recognize and teach these insights. In general, understanding the nature of art is still quite traditionally marked by discipline-like thinking, and otherwise undefined and even ambiguous. After all, the distinction between art and entertainment, or art and design, seems to be becoming less and less meaningful these days. Still, I think that my study of autonomous art has taught me above all how things can be 'images' of more general categories. How an 'image' may have something to say about the world and being in the world.

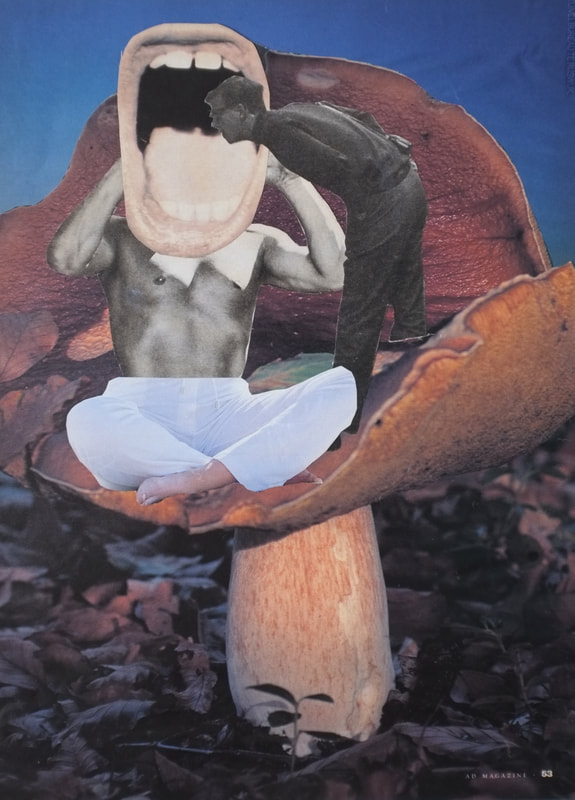

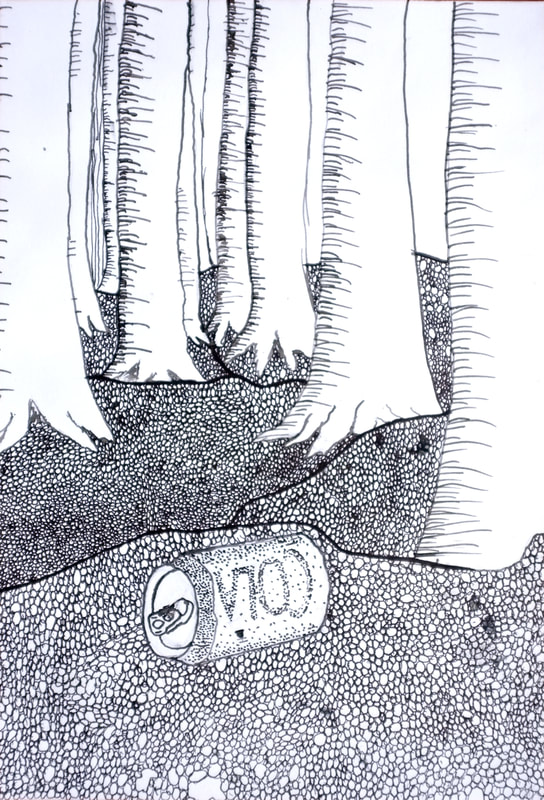

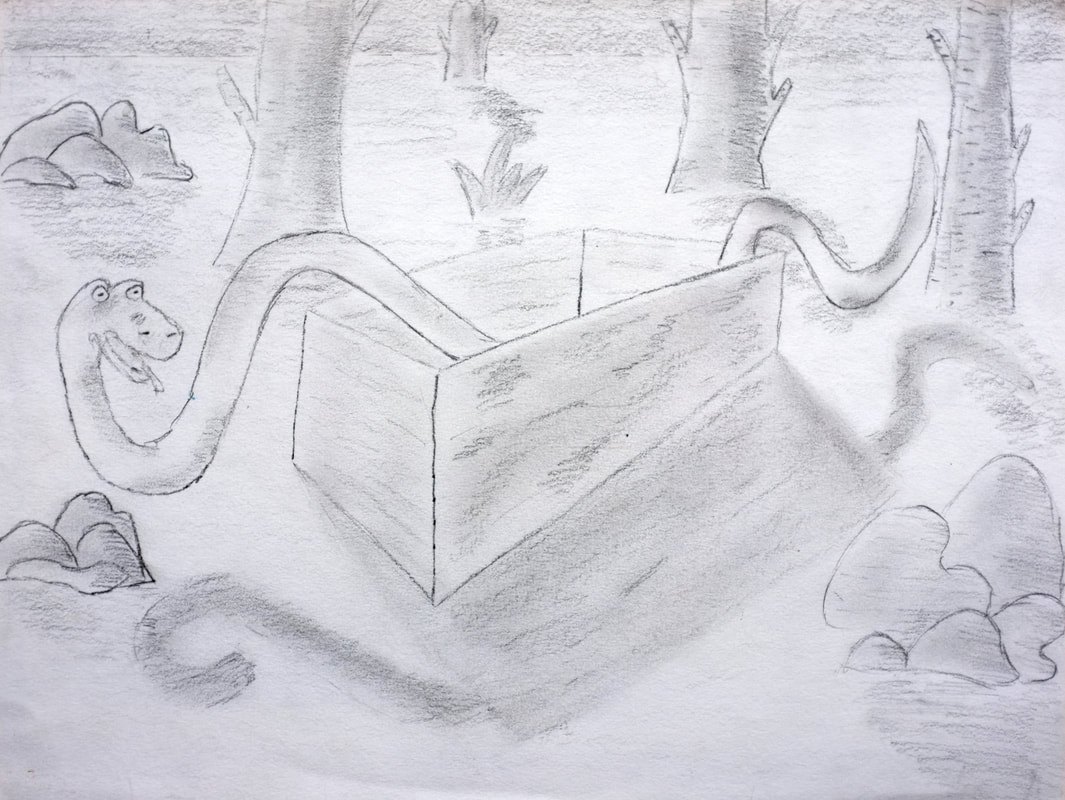

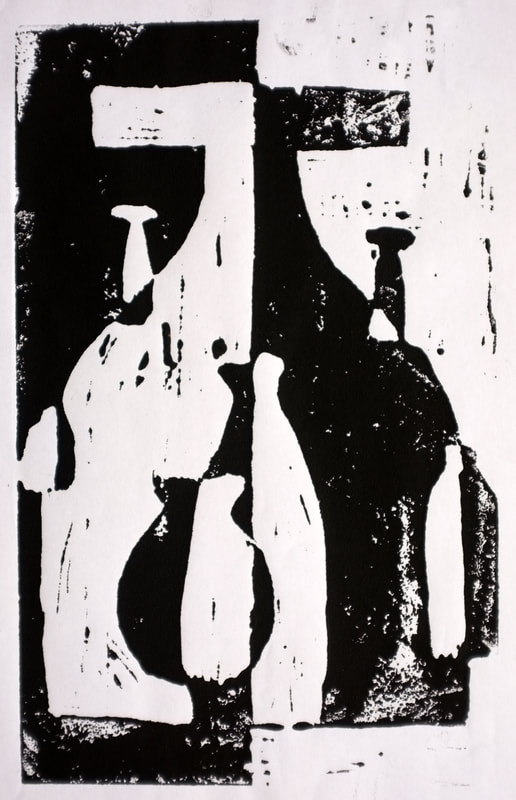

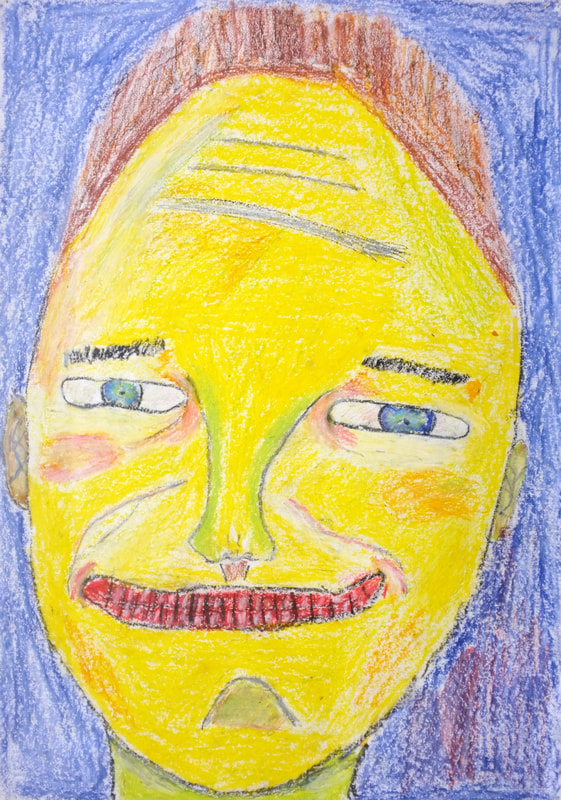

Of course, this insight existed already implicit in me when I chose to study autonomous art. This is reflected in work I did shortly before my application. The work is not just an imitation, but clearly aims to add something. Or, in many cases it is also non-showing and non-referential - a purely poetic 'description' that relates all kinds of things and aspects of the 'world' and being in the world in a meaningful way. This early work already makes it clear that even then I was already interested in what art can add to knowledge and insights, and not in a 'correct' or 'clever' application of skills and standards around the use of materials or forms.

During my studies at the unsurpassed Aki under the direction of Sipke Huismans, I never committed myself to any specific departments. Departments that were partly still defined by discipline-like thinking. I have always worked with teachers from different departments, from the photography department, the mixed media department and from media art, supplemented with the workshop assistant of the graphic department. I have graduated with work of mixed techniques - both spatial and two-dimensional, including video, film and audio - that I had brought together in an installation. As a contemporary (visual) artist I work in all kinds of art forms and with all kinds of materials or media. Throughout my artisthood, this has always been and has remained my practice.

Art theory has long since developed beyond the concept of art as mimesis via Heidegger, Arendt, Ricoeur and Gadamer. The theorists mentioned here, have sufficiently demonstrated that a work of art is not a doubling of reality (mimesis), but an increase. A work of art adds something that wasn't there before. Of course, it thereby puts that which is (already) in a specific relationship through its own, inalienable properties. By that I mean: the work of art is not a mere form, but is related in various, meaningful ways to the world around it - the world that preceded it, from which it originated and into which it enters.

What therefore remains of the 'visual' in visual art is the image as an example of more general categories. The 'image' says something about what it is or can be an image of. In the first place of himself, but, as Ricoeur so aptly put it: “In my opinion, all expressions are inevitably about something.” (Paul Ricoeur, Tekst en Meaning, Ambo, Baarn, 1991, p. 98) That 'something' is subsequently: the 'world' and being in the world. The latter means: how (it is or can be) to exist between everything that is and what we can know and think about that. But also, says Ricoeur: “besides the non-showing but still descriptive references, also the non-showing and non-referring descriptions.” (Work cited, same page) A 'world' is therefore something that is created through, with and in the expressions of people. People from now and before. An ongoing project.

But with this we are again removed from the specificity of the visual of visual art. The visual arts, in this new understanding, can no longer be identified with the term 'image' or 'visual'. In contemporary (visual) art we can now see that artists no longer limit themselves to what was previously and traditionally understood as the 'visual' disciplines or media: painting and drawing, sculptural or spatial art, and the new media of film, video, 'digital' forms and installation art. Contemporary artists work just as well with language, with movement, and with sound. The distinctive character of the 'visual' in visual art has been lost. The other art forms are just as 'visual' - in the sense of relating to 'seeing' as the development of insights - as the visual arts are, and vice versa.

Although the views of Ricoeur and the other theorists mentioned above, were largely articulated before the 1990s, they were not taught or discussed at the Academy where I studied. I also wonder who of the current professors and teachers at the various Academies for Visual Arts today know, recognize and teach these insights. In general, understanding the nature of art is still quite traditionally marked by discipline-like thinking, and otherwise undefined and even ambiguous. After all, the distinction between art and entertainment, or art and design, seems to be becoming less and less meaningful these days. Still, I think that my study of autonomous art has taught me above all how things can be 'images' of more general categories. How an 'image' may have something to say about the world and being in the world.

Of course, this insight existed already implicit in me when I chose to study autonomous art. This is reflected in work I did shortly before my application. The work is not just an imitation, but clearly aims to add something. Or, in many cases it is also non-showing and non-referential - a purely poetic 'description' that relates all kinds of things and aspects of the 'world' and being in the world in a meaningful way. This early work already makes it clear that even then I was already interested in what art can add to knowledge and insights, and not in a 'correct' or 'clever' application of skills and standards around the use of materials or forms.

During my studies at the unsurpassed Aki under the direction of Sipke Huismans, I never committed myself to any specific departments. Departments that were partly still defined by discipline-like thinking. I have always worked with teachers from different departments, from the photography department, the mixed media department and from media art, supplemented with the workshop assistant of the graphic department. I have graduated with work of mixed techniques - both spatial and two-dimensional, including video, film and audio - that I had brought together in an installation. As a contemporary (visual) artist I work in all kinds of art forms and with all kinds of materials or media. Throughout my artisthood, this has always been and has remained my practice.

|

TK 25-03-2022

|

Work from before I started studying at the Academy: 'The Black Road', oil on paper, 1990; Untitled, mixed media on paper, 1990; Heartland, Indian ink and gouache on paper, 1990.

I wasn't the boy that liked to draw and then walk up to my father or grandmother with it: look what I've made. Nor was I the boy who drew for the sake of drawing. I was interested in the drawing.

I have always remained that boy. I don't get my energy from 'making' or showing. I don't like having to go public as a person or having to 'sell' my work. These urges do not come from me, nor from my work, but from my environment. People sometimes seem to expect that an artist likes to be in the spotlight and politicians want me to enter the art market as an entrepreneur.

So for me it is not about making and certainly not about showing. It is about doing the work. This doing is not a blind activity of natural forces or instincts, it is intentional. Through, with and in art, I hope to gain insights and knowledge. In very basic terms, I want to learn and understand what exists in the world, how it exists and what it does, and what it means that it exists in the world - which in turn consists of a multitude of other cases. I also want to see and understand how, what and who we are and can be, and how we can be in a world - rather than just going through successive situations. I want an origin and a context that have a certain permanence, and (co)build it with everything I have ever read, seen and heard - and with what I do with that and add to it.

However, the tension between doing the work and how this is understood by others is precarious. Because part of doing the work is seeing how it works with others rather than with myself. When it goes wrong, people look at me as the maker rather than at the work. Or the value that the work represents on the art market is looked at instead of the work. Personally, I want to look together with other practitioners of contemporary art at what our work does and can mean. For I address that practice in my work. From that shared practice come the values that I strive for in my work, and with my work I want to expand and explore the possibilities of this practice. When my work is approached as merchandise, as decoration, as entertainment or from an idea of craftsmanship, it does not work. If I am looked at instead of my work, the work does not work at all.

And yet this is what often happens when I show my work...

I have always remained that boy. I don't get my energy from 'making' or showing. I don't like having to go public as a person or having to 'sell' my work. These urges do not come from me, nor from my work, but from my environment. People sometimes seem to expect that an artist likes to be in the spotlight and politicians want me to enter the art market as an entrepreneur.

So for me it is not about making and certainly not about showing. It is about doing the work. This doing is not a blind activity of natural forces or instincts, it is intentional. Through, with and in art, I hope to gain insights and knowledge. In very basic terms, I want to learn and understand what exists in the world, how it exists and what it does, and what it means that it exists in the world - which in turn consists of a multitude of other cases. I also want to see and understand how, what and who we are and can be, and how we can be in a world - rather than just going through successive situations. I want an origin and a context that have a certain permanence, and (co)build it with everything I have ever read, seen and heard - and with what I do with that and add to it.

However, the tension between doing the work and how this is understood by others is precarious. Because part of doing the work is seeing how it works with others rather than with myself. When it goes wrong, people look at me as the maker rather than at the work. Or the value that the work represents on the art market is looked at instead of the work. Personally, I want to look together with other practitioners of contemporary art at what our work does and can mean. For I address that practice in my work. From that shared practice come the values that I strive for in my work, and with my work I want to expand and explore the possibilities of this practice. When my work is approached as merchandise, as decoration, as entertainment or from an idea of craftsmanship, it does not work. If I am looked at instead of my work, the work does not work at all.

And yet this is what often happens when I show my work...

|

TK 31-03-2022

|

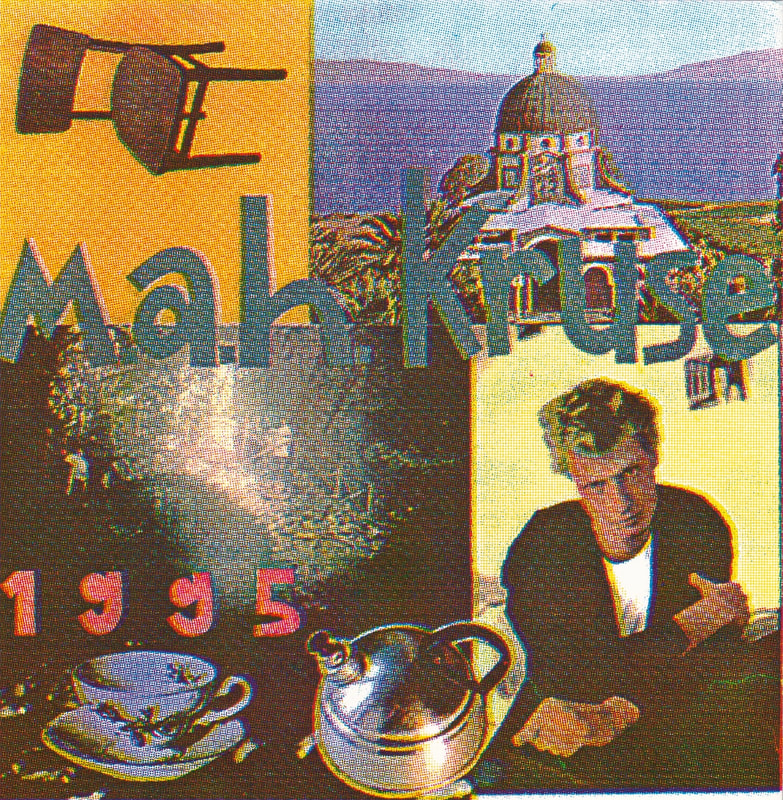

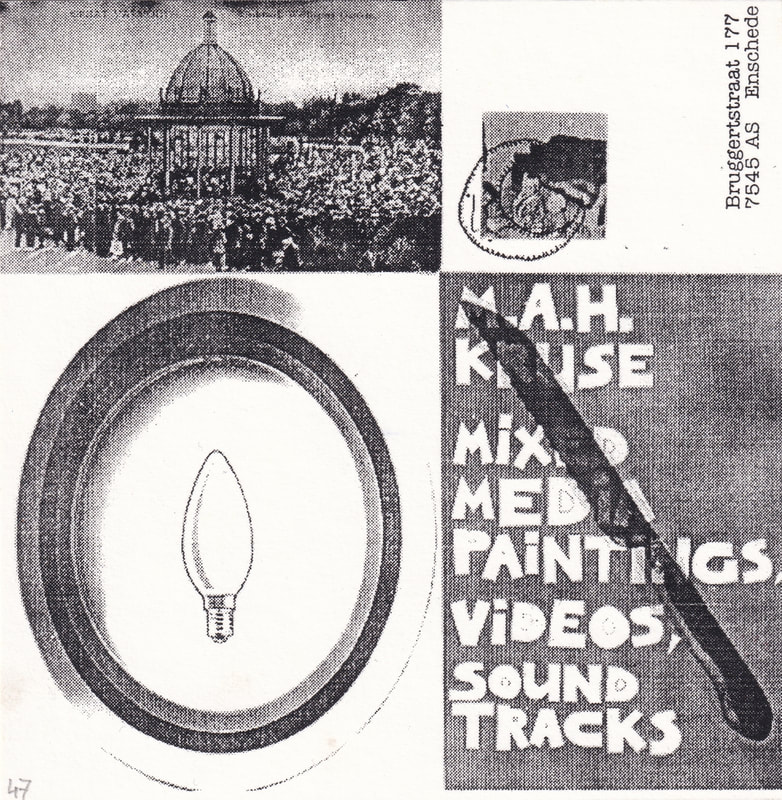

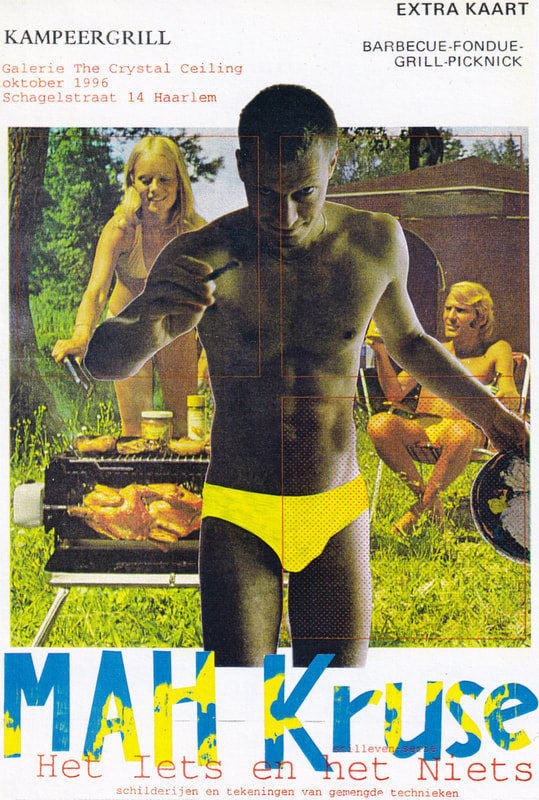

Invitations for: my graduation exhibition, 1995; my first gallery-solo, 1996; and the international media art festival, 1996.

In my work in secondary education and higher vocational education, as a teacher of art subjects, cultural and artistic education and art history, I have worked with various colleagues. Because the definition of the nature of art and the objectives of these varied subjects in education are a hybrid of different views and interests, there are also different and divergent interpretations of teaching in these areas. I had colleagues, for example, who actually did "crafts" with their classes: at the end of an assignment, the whole class had done exactly the same "craft" - every student did the same thing, in exactly the same way. I also had colleagues who used the subject as a kind of leisure time, where there was a lot of room for social interaction, affirmation and sociability. And there were colleagues who mainly focused on learning technical skills or who approached art history as a coherent evolution with a clear direction, the grand narrative of -isms. My criticism of all these approaches stands apart from my appreciation of the good and beautiful results they achieved. Results that, in my opinion, however, are placed outside the realm of art, as I understand it. Art as a practice of the acquisition of knowledge through the contemplation and actualisation of experiences.

Of course, people do not automatically become artists or art practitioners. They have to learn. Above all, they must learn what art is and how it works. In history, this was not an eternal truth, by which I mean that contemporary art is a different art from modern art, and certainly a different art from the art of antiquity or the Middle Ages. Contemporary art and modern art has been the starting point in my teaching. My goal as a teacher was to teach pupils and students what art is and how it works.

Art is a practice that must be done - even contemplating art is not a passive application of knowledge nor a subjective interpretation of purely individual feelings. One needs to engage with a work of art. Whether one does it or contemplates it, one needs to 'do' the work. But, unlike a science subject, the knowledge that is gained in the process of doing art - of that what the work 'brings up' - is not simply 'true' or 'correct'. The truth or accuracy of what is learned through, with and in the work of art must be tested. In the first place against the work itself, but also against the insights of others that were formulated by, with and in that same work. This is the discourse.

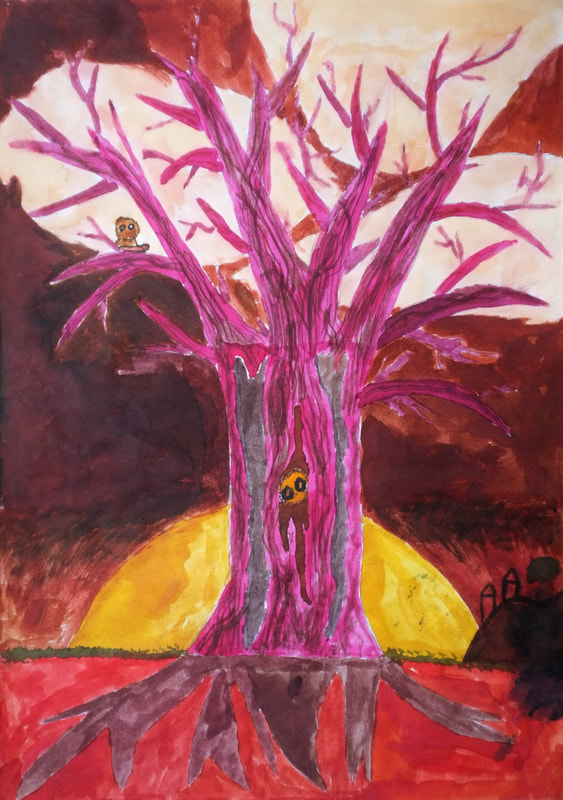

In a society where this insight is not very much alive, and where the concept of 'knowledge' has been narrowed down to what is found in natural sciences, it is not easy to teach pupils and students what practising art is and can be. In my experience, it pays to take small steps and work from concrete works by one specific artist. The practical organisation of teaching art to large groups makes it necessary to set limitations on the use of tools and media. But within the limitations, I found the space to allow children and young people to do their own work. As a result, there were no 'crafts' done, but each pupil did his own, individual work in my lessons. Divergent results arose in this way within an assignment or project, also when studying art history topics. As a result, my pupils worked and studied, and the subject was not a mere free space for affirmative social interaction. I also hope, but this is not a result that is achieved with every pupil or student, that it was not mainly techniques and skills that were learned and practised in my lessons, but that it was learned what art is and can be - and within that, all kinds of specific insights about the subjects and themes that were raised in doing a particular work of art. In a certain, more fundamental sense, through my educational approach at least some idea, perhaps just a suspicion, was formed in my pupils and students, about what art is and can do. In my experience, to achieve this it is important to always discuss the work that is being done, with the group or individually. Pupils and students often only then learn to 'see' what they have done. The conversation and tried and tested reflection produces knowledge and insights, and this is the practice of art. Not knowledge of how something is done, but knowledge of how something exists and works - and of what that means in and from different perspectives.

Of course, people do not automatically become artists or art practitioners. They have to learn. Above all, they must learn what art is and how it works. In history, this was not an eternal truth, by which I mean that contemporary art is a different art from modern art, and certainly a different art from the art of antiquity or the Middle Ages. Contemporary art and modern art has been the starting point in my teaching. My goal as a teacher was to teach pupils and students what art is and how it works.

Art is a practice that must be done - even contemplating art is not a passive application of knowledge nor a subjective interpretation of purely individual feelings. One needs to engage with a work of art. Whether one does it or contemplates it, one needs to 'do' the work. But, unlike a science subject, the knowledge that is gained in the process of doing art - of that what the work 'brings up' - is not simply 'true' or 'correct'. The truth or accuracy of what is learned through, with and in the work of art must be tested. In the first place against the work itself, but also against the insights of others that were formulated by, with and in that same work. This is the discourse.

In a society where this insight is not very much alive, and where the concept of 'knowledge' has been narrowed down to what is found in natural sciences, it is not easy to teach pupils and students what practising art is and can be. In my experience, it pays to take small steps and work from concrete works by one specific artist. The practical organisation of teaching art to large groups makes it necessary to set limitations on the use of tools and media. But within the limitations, I found the space to allow children and young people to do their own work. As a result, there were no 'crafts' done, but each pupil did his own, individual work in my lessons. Divergent results arose in this way within an assignment or project, also when studying art history topics. As a result, my pupils worked and studied, and the subject was not a mere free space for affirmative social interaction. I also hope, but this is not a result that is achieved with every pupil or student, that it was not mainly techniques and skills that were learned and practised in my lessons, but that it was learned what art is and can be - and within that, all kinds of specific insights about the subjects and themes that were raised in doing a particular work of art. In a certain, more fundamental sense, through my educational approach at least some idea, perhaps just a suspicion, was formed in my pupils and students, about what art is and can do. In my experience, to achieve this it is important to always discuss the work that is being done, with the group or individually. Pupils and students often only then learn to 'see' what they have done. The conversation and tried and tested reflection produces knowledge and insights, and this is the practice of art. Not knowledge of how something is done, but knowledge of how something exists and works - and of what that means in and from different perspectives.

|

TK 14-04-2022

|

Examples of work by my pupils from the lower years of Secondary Special Education, 2000 - 2008

Boys don't cry, was one of the sayings with which we were brought up. As a boy, I thought that was terribly unfair: because why shouldn't boys be allowed to cry when they were in pain or sad - but girls are? Presumably some would say today that we grew up with a "toxic masculinity," a toxic, or poisonous idea of masculinity. Such values and ideas were instilled in me not primarily in our family, but primarily in the environment where I grew up. Why were boys not allowed in the home corner? Why should boys prefer to want to play with building blocks or toy cars? Why shouldn't boys like dressing up? Why should boys think girls are "stupid"?

I am very grateful for my parents and grandparents, who offered me a protective environment in which I was allowed to play with dolls (including 'girls' dolls') and in which it was not girlish if I ever needed to cry. But of course the protective home-world can and should never completely exclude the outside world - and so I still found myself in an environment where my natural and individual character and interests were put under pressure. I experienced the normative socialization of the common denominator of our village society - the somewhat less educated and intelligent, but largest group - as judgmental and excluding. 'Being yourself' was not unconditionally 'normal' for me.

For me, the prescribed roles and preferences of boys were oppressive and judgmental, but it was not so that I particularly identified with the prescribed roles and preferences of girls. There were also " boys' things" that suited me and that I liked to do. What people nowadays often say about gender roles, but then often from a more sexual perspective, is that they are fluid, liquid. For me, in my village, the strict delineation of what would belong with boys and what would not - of how I should 'be' - was unfair and not fitting: toxic. I faced exclusion and bullying. But I was at the same time given the space by my parents and the teachers at Primary School to respond to my individual character and interests, and still become 'who I am'. But this 'me' got trapped in the normative outside environment and was there much unsafe. I was fearful of bullies that could attack you for no reason, just for being yourself and, for example, looking for ladybugs or playing with a girlfriend.

As a boy with a strong and large imagination that quickly became bored with the endless tasks with twelve rows of exactly the same exercises, I scored lower on arithmetic in the Final Test of Primary School than my brothers - but higher on language and creative subjects. Yet this was the reason I had to start at the midlevel secondary school instead of the high level school, like my brother did. And I didn't encounter a teacher there, like my brother did, who came to tell my parents that I really should try a higher level because of my high grades, which I did have. And to make matters worse, I ended up as the only Catholic boy at the Protestant midlevel seceondary school, an inimitable choice by my parents. None of that helped very much in finding the space to safely develop myself. In those formative years, I was always the weird outsider, doing things that none of the other boys understood. I liked weird music and did not listen the Top 40, I did not play soccer and had peculiar interests. Though I write it down lightheartedly here, it was a time of suffering, of unsafety and sadness.

When years later, after some detour (becoming oneself was still not a given for me), I began my studies in autonomous art, I faced another form of unsafety and exclusion. As a boy from a medium-sized rural village, who first came to the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam at seventeen because I (finally) had been able to choose art as a graduate subject - and who knew nothing about galleries, artists, and contemporary art beyond what I had learned in that graduate subject, I found myself among fellow students who had been raised with museum and gallery visits, and recitals of serious music. People who knew who our teachers were and what kind of work they had done. I went to live on my own for the first time in a strange and distant city where I knew no one, nor the way around - while many of my fellow students came from the region or city - and thus retained their social environment. Only years later I have really understood how much lag I really had to overcome in comparison to many of my fellow students, who did not need me in the same way that I needed them - and who did not greet my insecurity and uptightness with benevolence, but rather with ridicule and rejection. I really had to fight my way in.

These experiences have enabled me to deeply empathize with people who face exclusion and disadvantage in various ways. And although I have by no means always gotten it right myself, I have a strong and sensitive radar for social exclusion and discrimination on unjust grounds - namely: on the basis of conceptions of norms and values and the familiarity with ways of doing and states of affairs, prevailing within certain social groups. I have a radar for the social stratification that is still normative in the art world.

In Hannah Arendt’s, The Life of the Mind, I read that the Ancient Greek philosopher Socrates wanted to make the views of the people in the polis, their doxa, "more truthful" (p. 606, Ten Have, Utrecht, 2021), with fatal results. After all, Socrates was sentenced to drink the poison cup. Arendt explains that Socrates examined the views of the citizens of the polis, in dialogue, with the intention of helping to make visible the "truth" in them. For, says Arendt, everyone sees reality from a specific and individual position (p. 609). It is quite difficult to rise above that and name 'the true' from all divergent points of view. Where all these different views meet and overlap, we find what the inhabitants of the polis have "in common”. Socrates wanted to find that common "world" (community) by conversation, from the diversity of each perception of reality (p. 608).

The truth of that common world thus appears in a plural logos (word): logoi (p.609). But one can trust the words of others only from how one knows oneself, in your own thoughts. For in your thoughts you are also not alone, but with yourself. Your thoughts are a conversation (a dialogue) with oneself, even if you occasionally take an imagined position of another in them, against yourself and the issue you are thinking about and that you want to come to understand (p. 611). In this sense, you always have the others with you, as a representation in your own mind - and this imagined position also allows us to imagine from which position another sees reality - and to understand that point of view. When you (in your thoughts) contradict yourself, Arendt says after Socrates, you are therefore unreliable to yourself. For instance: A murderer knows of himself that he is capable of murder, and therefore he lives in a world of murderers (p. 613).

Socrates wanted to make the doxa, the opinions or views, truer - but politics (the "voting" citizens of the polis) turned against him (p. 616). Arendt then says that "the man of thought" opposes "the man of action" (p. 617). What the "thinker" thinks contradicts what common sense, the general opinion, thinks (p. 620). This is because, so says Arendt, the thinker (the philosopher - or the artist) questions what is 'common sense' to everyone else: we (artists, philosophers) know that we do not know (p. 624). The majority of people do not want to endurehat experience of, actually, speechlessness. Rather, people hold opinions (that's normal, that's how it should be done, that's just the way it is), even when they really should have kept quiet, simply because we don't know.

When I wrote about the unsafety I experienced in my youth, and later when I entered the art world, I am talking about this contradiction: the judgments and prejudices that prevail in a community versus the speechlessness of knowing that you don't know. Arendt therefore states that a philosopher avoids dogmatism (p. 626). Where I continue to question and remain open, the community has its judgment all ready. For myself, I cannot do otherwise, but my environment opposes this with its judgments and prejudices, and will experience me as contrary or nonsensical. Because they think they know.